John Aubrey’s Natural History, Part 5: Lead, Spar, and the Cure for the Stone

This blog discusses the historical use of lead. Lead is highly toxic. Please do not try any of the lead-based medicines I discuss below. If you have urinary stones, see a medical practitioner.

In his chapter on minerals in the Natural History of Wiltshire, John Aubrey combined his personal observations, knowledge, and experimentation with published sources, expert knowledge, local know-how, and a preoccupation with providing his readers with useful information. In this endeavour, he was particularly interested in human health. Every unusual earth, every mineral spring, every odd-coloured rock was potentially medicinal, including those that he suspected contained lead.

Aubrey perceived that there were no lead mines in Wiltshire, ‘nor can I well suspect where we should find any’, although he had been told there was lead nearby in Sodbury, Gloucestershire. Nonetheless, in his natural history manuscript on Wiltshire, he discussed the uses of the mineral. The metal held heat well, and he observed that stones from lead mines were used as bed-warmers, and joiners used lead for their glue pots. Lead could be converted to vitriol (sulphate) and back. And, although not commercially valuable, it was interesting as an experimentum luciferum, for knowledge’s sake, thus a light-bearing experiment. Aubrey noted too that lead produced the most salt of any metal, and could be used to make saccharum saturni, sugar of lead, a sweet-tasting, highly toxic substance historically used in medicine as an astringent or to treat diarrhoea. Although Aubrey did not suggest any usage of saccharum saturni, he noted the curing of an ‘ancient gentlewoman’ of his acquaintance who suffered from chronic diarrhoea and who had found no benefit from consulting physicians or using medicines they prescribed. She travelled to Wells, ‘being very ill’ and within a fortnight ‘grew very well of that distemper and so continued.’ Aubrey attributed this to the local ‘lead-water’—an opinion corroborated by Christopher Merret MD.

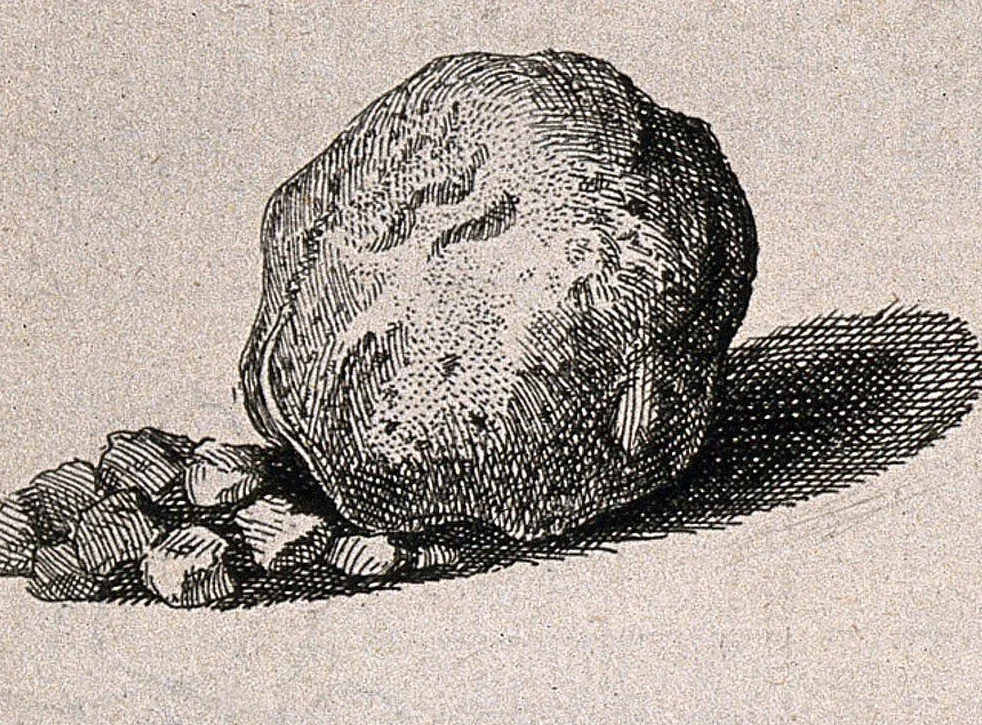

The most compelling section of Aubrey’s writing on lead, and probably of the entire chapter, is a story that unfolds across three decades and two countries and concerns a remedy for urinary stones involving powdered lead ore. Aubrey introduced it almost casually, as a ‘receipt’ (recipe) for stones. Powdered lead spar, probably referring to galena, a lead ore, as much as would heap on a coin, dissolved in Rhenish wine. He noted it ‘wonderfully causes one to make water...and to void the stone also.’ He added with characteristic brevity, ‘often tried.’ This cure had come from Sir John Gell, who lived in the Peak District of Derbyshire, one of England's most important lead-mining regions. Gell suffered from urinary stones, a dreaded affliction as the stones were agonising, recurring, and potentially fatal. Surgery—lithotomy—required being cut open without anaesthetic to have the stone removed. When a Frenchman appeared in the Peak District who took several loads of the spar, Gell’s interest appears to have been piqued. The Frenchman was clearly taking it back to France for a purpose—but what? The Frenchman finally told Gell, though the circumstances were not elaborated, and relayed the remedy for urinary stones. The black spar was best, the Frenchman said, and he had used it successfully in his medical practice in Paris. Presumably, Gell was cured by the recipe or at least appeared to be. Aubrey continued, ‘there was a report’ around 1680 that a ‘gentleman’ in London was afflicted with a kidney stone, presumably beyond bearing, as he had agreed to undergo a lithotomy. However, ‘ready for the knife,’ he was instead given ‘a certain blackish powder, not unlike’ the lead remedy. He took it. And the operation never happened.

The most detailed episode in Aubrey's account of lead and urinary stones began with a simple fact: an alderman of London had been using lead spar from the Peak District for his stones, and it had served him well. Then, in September 1686, his supply ran out. ‘He lay in great pain,’ and for whatever reason, could obtain no more. Then the story took an oblique turn. Kenrick, a pewterer, had in his possession a substance that Aubrey had given him for the purpose of making glass. This material, also described as spar, from Flamstone Down in Wiltshire, was not black but rather, transparent, bright and slightly yellow. It ran in striations, was extraordinarily hard until it broke, and, Aubrey suspected, contained tin or silver. Kenrick still had some left. He looked at it. He looked at the alderman's situation. He reasoned, with the pragmatic logic of a craftsman rather than a physician: ‘if it did the alderman no good, it could do him no hurt.’ He took the prescribed substance from the pewterer in the same dose as he had been taking. Half a drachm—about 1.8 grams—in a glass of Rhenish wine, fasting, once a day, until the patient was well. I confess I am not sure of the alderman's reasoning in accepting a remedy from a pewterer, but it worked - or appeared to. The result was not merely satisfactory. The Wiltshire spar ‘very much outdo that of the Peake, in so much that it perfected what the other had left undone.’ I have many, many questions about this, but unfortunately, Aubrey’s text then pivoted to another cure for urinary stones, Lapis Judaicus or the fossilised spine of certain sea urchins, a more commonly known traditional remedy for urinary problems, including stones.

The lead remedies look like madness from our perspective. But from Aubrey’s viewpoint, it was evidence-based medicine: multiple witnesses, repeated trials, measurable effects, expert endorsement. He was doing the best science he could with the tools and knowledge available to him. I am reminded that hindsight is a wonderful thing. It is easy to look back on the past and snigger. That Aubrey’s science happened to be toxic doesn’t make him foolish; it makes him human and historically situated. Aubrey’s instinct to document, to question, to compare, and to seek out ‘what works’ was admirable; even when he got the answers wrong, he was asking the right questions.